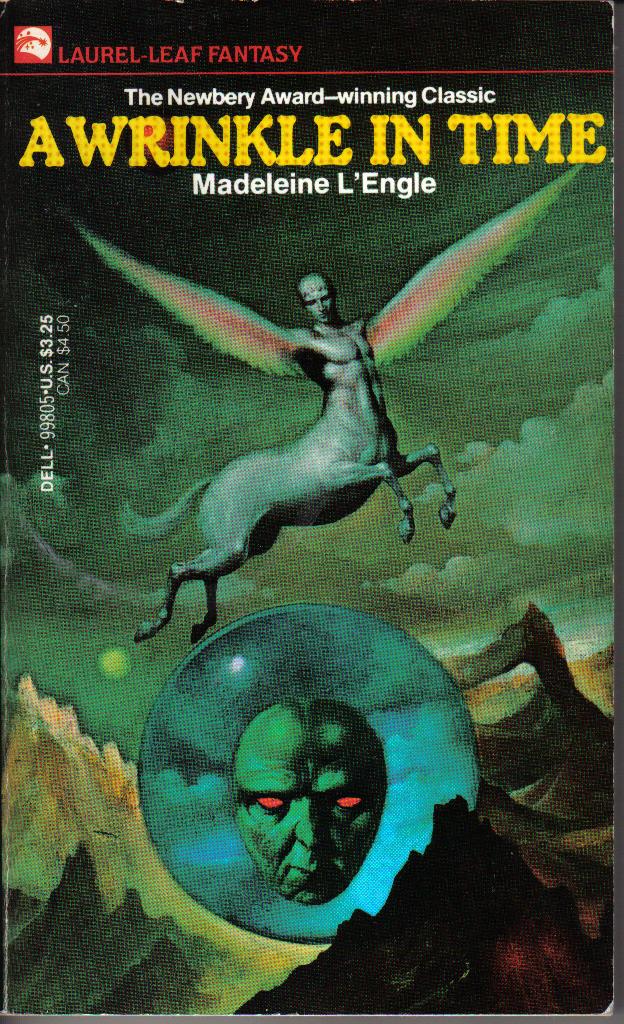

Having cried all over the WRINKLE IN TIME trailer, I thought I’d better re-read the book immediately to get a proper feeling for it again. It’d been at least twenty, possibly thirty, years since I’d read it, and…

…it’s kind of equally weirder and more mundane than I remember it.

I was prepared for, although somewhat exasperated by regardless, the Christian allusions; whenever I last re-read L’Engle, I was adult enough to notice her books are really laced with Christianity, so I knew that was going to be there. The story itself is actually a lot more straight-forward than I remember it being; possibly I’ve conflated the other books with it, or maybe it’s just that the weird bits are SO STRANGE that I thought the story structure had to be a lot more complicated than it really is.

It’s not, from a modern storytelling perspective, especially well told. It takes about four chapters to really get going, and it’s only a 12 chapter book. There’s a lot of telling, but not much in the way of showing in terms of…*why*. Meg is not, to the adult modern reader, particularly sympathetic: she doesn’t fit in at school, she’s angry in general and specifically very defensive about her father’s absence, and is apparently some particular kind of dumb that excludes being spectacularly good at math. That dumbness may be meant to indicate she’s socially inept, but although that certainly appears to be true, it doesn’t seem to be what’s really going on.

But that…dumbness…whatever it is…is crucial through the whole book. Meg doesn’t tesseract as well as the others. Meg is more vulnerable to the Darkness than the others. Meg won’t understand if you explain the thing…but I never understood why. (I’m not sure I understood as a kid, either, but it didn’t matter as much to me then.) And it’s apparently not something that came on simply because Mr Murry disappeared, because even he comments on it, and had done so before his disappearance, so you can’t lay her anger/ineptitude at the feet of her father’s disappearance.

And, just as much as Meg’s lack is not explained, neither are Calvin and Charles Wallace’s aptitude. Calvin communicates well; well, okay, that’s fine, but why does it make it easier for him to tesseract? Charles Wallace is, as far as I can tell, not even actually human, and Calvin, who does not come from the Murry family at all, is apparently More Like Charles than Meg is. But I don’t know what they are, or why they are, or why they’re the special ones and our heroine isn’t (well, that last one is institutionalized sexism, but let’s move past that). I remember *loving* Charles Wallace (and crushing terribly on Calvin), but I find him fairly creepy now, and that’s as the parent of an extremely self-assured little kid who, like Charles Wallace, is quite certain he’s able to Do It His Way without listening to the wisdom, or at least the experience, of his elders.

The one thing that maybe felt the most true to me in the whole book was Meg coming around to being the one who can save Charles Wallace. She wanted someone else–her father, specifically, but ANYBODY ELSE–to have to do the hard work. She was terrified and resentful of having to do it herself (and possibly that’s what the aforementioned “dumbness” is, since everybody keeps saying If you’d only apply yourself, Meg,, but that still doesn’t explain why she doesn’t tesseract as well, etc), and that seems very appropriate to a 13 year old to me. To people a lot older than 13, too, for that matter. But it comes in the 11th hourchapter, and her willingness to go on there is the only time in the book that she moves forward of her own volition. I’m not saying that isn’t fairly realistic, maybe, for a young teen, but in terms of making a dynamic book, it…doesn’t, really.

There are parts of the book that remain wonderful. The Mrs W are still splendid; Camazotz (which I always read, name-wise, as being what happens when Camelot goes terribly wrong) is still EXTREMELY CREEPY, and the thrumming presence of IT remains startlingly effective. Aunt Beast is wonderful. (So basically: the aliens work a lot better for me than the humans do.)

It doesn’t feel like a book that could get published now. It would need more depth; it felt shallow to me. A lot of its weirdness seems to me like it came very specifically out of the 50s and early 60s; I don’t think that book would, or perhaps *could*, be written now. It’s very internal in a lot of ways, and I’m really looking forward to seeing how the film adapts the weirdness and the internalness and Meg’s basic lack of agency into an accessible story. My *feeling* is that they’re going to do a magnificent job of it, that it’s going to be one of those cases like Frankenstein or Jeckell & Hyde where the book’s conceptual foundation proves more powerful in film than it does on the page. I hope so!

But you know what I really wanted to do when I finished reading A WRINKLE IN TIME? I wanted to re-read Diane Duane’s SO YOU WANT TO BE A WIZARD, because I felt like the Young Wizards books use A WRINKLE IN TIME as a conceptual springboard and dove off into something that worked a lot better as a *story*.

So I guess I know what’s up next (or soon, anyway) on the Catie’s Re-Reads list. :)

Interesting. I haven’t reread the books for years, although I probably read them a dozen times when I was younger. Now I’m a little afraid (although I do vaguely remember them getting better throughout the series). Didn’t the first one win an award of some kind?

And I agree about the Wizard books, which I love to pieces.

So timely (for me) that you wrote this. My 13 year old daughter was ‘assigned’ this book by me, as we have a book-before-movie rule in our house (thanks JK Rowling & Harry!). She was insistent that I reread with her. I confess to much of what you responded here – it was not as I remembered. I was not swept away. I kept thinking, I like the O’keefe family series better, but now I am afraid to re-read Arm of a Starfish etc. in case I no longer love them.

Ah, but probably more importantly: what did your 13 year old think? :)

You’re the second person in two days who has attributed some (or all) of the weirdness in A Wrinkle in Time to “the 60s”, which, for someone who was born in the 50s and first read the book as an adult, is…fascinating.

Anyway, I started a reread yesterday, as my “gym book. We’ve just picked up Calvin, and gone through the whole “sport” conversation. Since I don’t read fast anyway, and even slower than that when I’m walking on a treadmill, this will take a while, but I’m thinking that’s not a bad thing.

I have read the book a couple of times, but the last time was probably 20 years ago.

I do have to say that, so far, I’m not finding the 60s as depicted any weirder than they actually *were*; and (so far at least) the kids are holding up better for me than, say, the kids in Heinlein juveniles.

I haven’t read a Heinlein juvenile in a loooong time. I wonder if I should. :)

Having not been there for the 60s myself, AWIT doesn’t seem any weirder than my perception of the *rest* of the 60s, but it does seem like something born from that era. :)

I’m dyslexic, and Meg’s dumbness has always read remarkable true to me. I was in my second year of a PhD program before it occurred to me that I was actually smart, not dumb. I always, and still do, read this as Meg had a learning disability too, but here went undiagnosed because her Mom was on tilt with her Dad’s disappearance and wasn’t able to do battle with the school the way my parents did for me. Having lived through several years of elementary school where my peers called me stupid and my teachers seemed to think I just wasn’t trying, Meg’s passiveness also made sense. When I was diagnosed at 8 almost 9, I was on the verge of giving up and becoming a lot more passive about life. If I’d hit 12 undiagnosed and without the extra tutoring and support I got for dyslexia I’d have been Meg. A Wrinkle in Time has always read to me as a story about what it takes to function when your brain works just a bit differently then those around you, with the hardest lesson being that you can’t rely on anyone but yourself to cope with your own limits, but that your limits can teach you strength and perseverance if you let them. Perhaps because my perspective on Meg is so different, I found that I still love this book as an adult.

I still liked it very much, but found it less satisfying than as a kid. :)

It did occur to me while writing this that Meg might be somewhere on the autism spectrum, which in 1963 there wouldn’t have been much language for. A learning disability sounds even more probable to me, so thank you for that perspective!

(Another friend posits that Charles Wallace is *definitely* autistic, although I actually disagree with that, largely because I have a friend who, much like Charles Wallace, didn’t start speaking until he could do so in full sentences at about around age 3. To me the fact that he doesn’t talk to people outside of his family seems to have a lot more to do with most of his family being barely able to keep up with him, and everybody else clearly just being not worth his time, but to me all of that, plus his telepathy and whatever else, falls under “Charles Wallace isn’t really human,” which could be a terrible way to percieve autism, but I think he’s *magic*, not autistic…)