Once in a while I manage to have my act together enough to present a holiday short story to my readers. This year’s story was inspired by visiting North Carolina for the first time, and driving some of those twisty twisty roads that Joanne is so fond of.

Slaying the Dragon is set five years after the end of SHAMAN RISES, and as such, contains, if not outright spoilers, certainly spoilers by association. :)

Slaying the Dragon (pdf)

(turns out wordpress won’t let me upload epub or mobi files, sorry. you can always subscribe to my Patreon if you must have the e-reader friendly files. :))

Story behind the cut!

Slaying the Dragon

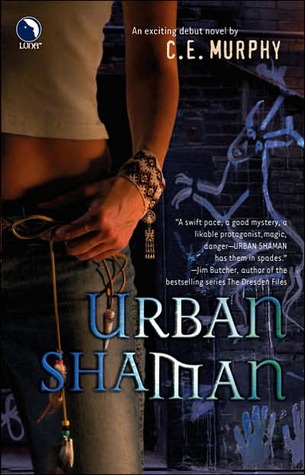

A Walker Papers short story by C.E. Murphy

The Dragon, Great Smoky Mountains: 10:57pm, Yesterday

Three hundred and eighteen curves in eleven miles, the sign read. The Dragon, twistiest road in the Smokies, or close enough to count, anyway. I hadn’t run it at night since I was a teenager, but this time I had the lights on and there was a full moon. Easy peasy. “Do you trust me?”

Morrison jammed his feet deep enough into Petite’s passenger-side footwell to damn near set his shoes to smoking against the front wheels even though we were only climbing through the warm-up stretch in the Tennessee hills. “No. No, I do not. Absolutely not.”

“Yes you do,” I said cheerfully. “Or you wouldn’t have gotten in the car with me in the first place.”

“You said ‘It’s a nice day, Michael, let’s go for a drive, Michael’ not ‘Let’s speed through breakneck curves on ten-foot-wide roads in a car older than I am and then do it again in the dark, Michael!'”

I leaned over, kissed him, said, “You will never convince me that you didn’t know what you were getting yourself into, not only because you’ve known me for almost ten years now, but also because I remember the entrance you made up in the hills when we were going after the Raven Mocker,” and threw Petite into gear, punching the gas as Morrison howled, “I was driving then!”

“There are whole sections of the Dragon where the speed limit is 55!”

Morrison screwed his eyes shut and swore. I laughed and leaned in to the first really big curve, half letting my 1969 Mustang drive herself. She and I had cut our teeth on these roads two decades earlier, and there still wasn’t a stretch of hill country I couldn’t navigate with my eyes closed. More literally than not, these days, since when I was a kid I hadn’t been able to use the Sight, a magic-born second vision that lit the whole world with purposeful light when I activated it. Even if I’d been able to as a teen, I probably wouldn’t have, but I was old enough now to appreciate how long dead lasted. I was A-OK with using every skill available to me, not that I was going to tell Michael that.

Besides, just like most roads, the Dragon wanted motorists to stay on it. Things were imbued with purpose, whether because humans had built them for those purposes or because they’d grown that way. Buildings shone deep green with the desire to shelter, trees flowed with the electric white-blue light of sap flowing through them as they made air for us to breath, and roads glimmered with the wish to get people safely from one place to another.

Mostly, at least. In places, the steady depth of color shifted from rich deep purposeful blue toward a sickly shade of purple, and even into black. A lot of people had shot off the road and tumbled down the mountainside, or smashed into a mountain wall, in those places. Enough to make the Dragon forget its basic impulse to get people where they needed to go, so those were the places I slowed down, even if taking some of the other curves at improbable speeds made Morrison mutter prayers I hadn’t even realized he knew.

But Petite was built for speed, low-slung and heavy and with an engine that would torque a lesser vehicle right off the ground. I kind of wished I could see her from the outside, purple paint job turned glittering black under the moon as she clung to the curves at forty-five, fifty, sixty miles an hour. She pulled at my hands as we slung ourselves down the center line, throwing us back into leather bucket seats as I braked and downshifted, and sucked us against her doors as we tilted around a series of switchbacks that made me cackle with glee. We hit a short straight stretch and I glanced at Morrison, who was either grimacing or grinning, it was hard to tell. Definitely a grimace when I got us up to eighty before braking hard at the upcoming curve, but he didn’t say a word. Probably afraid if he distracted me I’d drive us off the road, and while I’d once built a bridge out of magic, I’d also sworn I would never do any such thing again, what with it having wiped me out for about three days. Not to be recommended.

Trees closed overhead, blotting out the moon. I wanted desperately to turn the headlights off, to speed along in the dark with the roar of Petite’s engine as the only link to the outside world, but I thought Morrison might actually have a heart attack if I did that. I did say, “It’s like flying,” out loud, although softly enough I didn’t think he would hear.

“It’s like a damn shuttle launch, Walker.”

A grin split my face. “Technically, that’s flying.”

“Technically, you’ll lose your license if somebody catches us.”

“Nobody ever has.” I turned the headlights off after all, because if I was gonna get scolded I might as well really enjoy myself.

Darkness swallowed us up, a warm summer embrace. There were hardly any lightning bugs left this late at night, but a few scattered through the corners of my vision, momentary streaks of gold like the Dragon’s fire sparking in the air. Moonlight shafted on the road ahead, announcing a break in the trees, and when we flew out from under cover, for a moment a whole valley view opened in front of us, blue-green in the pale light, mist gathering in patches and fading away again. Dragon’s breath, in and out, though I swore I’d never romanticized the name before magic had marched into my life almost ten years earlier. Back then it was just a name, a dragon for all its twisty turns, like a serpent’s tail, not because I half-imagined there might be some kind of mythical creature out there in the hills. I still didn’t, but it was easy to dream it, now.

“Walker.”

“I am using the Sight, babe.”

“Oh, well, then, have at.”

I could feel his glower, and, grinning, reached for the lights. He didn’t exactly relax, but he exhaled, at least. I said, “Sorry,” with a degree of sincerity, and, “Holy shit,” with a whole thermometer of it.

***

There were no goddamn dragons in North Carolina. Or Tennessee, since that’s where we still were, having not yet crossed the state line, but wherever the hell we were, there weren’t supposed to be dragons there. There weren’t supposed to be dragons anywhere.

Uktena, said the back part of my brain. Not a dragon. Not exactly. A serpent, albeit with vast, buzzard-like wings that shifted and shone in the moonlight like they couldn’t decide if they were covered with reflective scales or oil-slick rainbowed feathers. Nasty, curved prongs rose from its forehead, stretching wide into antlers the biggest buck would be proud of. Between the antlers sat a fist-sized stone streaked with purplish-red.

It was six feet tall at the spine, and had the slenderest neck and pointiest, most leaf-like head I’d ever seen on a snake. It slithered onward, unconcerned, as I hit the brakes. Rubber burned and we fishtailed and swung around until Petite’s back end bumped the monstrous beast’s side. It paused, looking back at us with eyes of burnt ember. I slapped my hand over Morrison’s face and closed my own eyes, though I could still see it perfectly well with the Sight. Better, maybe: in boring old moonlight it had an ordinary snakeskin pattern, but with the Sight it ran deep into colors no Appalachian snake I’d ever seen wore. Gradients of blue glowed along its backbone, shading to indigo and then switching to a sudden, vibrant orange that patched between violet diamonds before its belly went to bright, ridiculous yellow.

Morrison said, “What the—?!” but he didn’t make any effort to move my hand, while I went through a mental scramble about what seeing an uktena meant. Something bad, but I couldn’t remember if it was basilisk-like and meeting its eyes would turn a person to stone, or—

“No,” I said out loud, even though the first part had been to myself, and dropped my hand. “It’s safe to look at, I mean, it’s not, but it’s too late now—”

“Joanne,” Morrison said with something approaching infinite patience, and then neither of us said anything as the uktena slid over the edge of the road and into the greenery. Only when it was gone did Morrison turn his gaze on me, not afraid, just waiting, and I couldn’t help smiling at him. He was eleven years older than me, in his mid-forties now, but he’d been silver-haired since I’d met him, having gone grey early. The tan he’d earned out tromping around the hills with me made the fine lines at the corners of his blue eyes more visible, but even in moonlight—maybe especially in moonlight—those eyes had the clarity of a mountain pool.

I said, “I love you,” and amusement creased the corner of his mouth.

“I love you too. What was that thing?”

“Uktena.” It occurred to me that we were parked, as it were, across the middle of a two-lane highway full of notorious curves. I’d killed Petite’s engine with the sudden stop, and revving her up again was shockingly loud against night sounds that had faded into cricket song and wind. “Cherokee monsters. They say the first one was made of a man who tried to kill the sun and failed.”

After a moment’s silence, Morrison, deadpan, said, “I can see how that might have been difficult, yes,” and for a woman who’d grown up rejecting the Native half of her heritage, I found myself giving him a surprisingly dirty look. Dirty enough that Morrison chuckled and said, “Well, it would have been. What’s it doing up here?”

“Along the Dragon? Probably giving it its name.” I pulled Petite back into the lane and sat a moment, trying to think of where we were on the road and where an overlook might be. The nearest one was behind us, but I didn’t especially want to turn back. “The old stories say they live in lonely mountain passes and deep river pools.”

Morrison glanced over the shoulderless edge of the road. “We’re a long way up from the rivers.”

“Definitely got the mountain pass part of things, though.” I ran a hand through my hair, sending it into spikes, and frowned at the road. “Stories say the families of those who see an uktena will die, if you don’t defeat it.”

Morrison held his breath a moment. “Aidan.”

“Aidan,” I agreed. “My dad. Your mom.”

“But mostly Aidan.”

I spread my hands against the steering wheel, feeling the engine’s rumble reverberating back through my palms. We hadn’t gone anywhere yet and really, I didn’t expect us to. “He’s only nineteen. I don’t want to risk any kid’s future by disbelieving the myths.”

“I know.” Morrison fell silent. “You sure about the legends?”

“My experience with them,” I said a little bitterly, “is that they’re generally true.”

“Yeah.” Morrison sighed. “Only you go on a joyride that ends in a monster hunt. How do the stories say you kill an uktena?”

“Ah. Well. Traditionally, by tricking tlanuhwa into destroying it.” I cast a sideways glance at him. “Not unlike a thunderbird.”

Morrison’s expression darkened. “We’ve done thunderbirds already, Jo.”

“Well, the good news is that great heroes are also supposed to be able to kill them, although there aren’t any specifics on how.'” I sucked my lower lip in, thinking. “The better news is that I’m pretty sure that jewel on its forehead is supposed to be irresistible, that it makes even great heroes walk right down the uktena’s gullet, and I didn’t feel any compulsion to do that. They’re supposed to be focal points, too. Power sources. You can work great magic with them.”

“Are we going on a monster hunt or a scavenger hunt?”

“A little bit of both.” I sighed and pulled Petite to the side of the road, not that there was much side to pull her to. More like almost enough space between some trees for her length and almost enough green-covered depth before the mountain fell away to the side for her width. There were pullouts all over the Dragon, but not one here where I needed it. Before Morrison asked, I said, “Yeah, I’m going to leave her here, because if we drive up to the next pullout we’ll lose the uktena. Besides, woe betide the fool who touches my baby.”

Morrison, fondly, said, “Pathological,” and I smiled at him before shooing him out of the car and locking her door behind him. He went around to the trunk and opened it while I got out, and was gazing down at the array of weaponry available to us when I joined him. “What do you hunt snakes with?”

“A two-pronged stick and a club.” Clubs I had, although no stick short of an actual tree would be big enough to pin the uktena down. “Failing that, how about a shotgun?”

“It’s a start.” Morrison took out a shotgun and a couple knives, holstering them with the confidence of long experience. I thought it was sexy as hell, which with the moonlight and the fireflies and all could have led somewhere wonderful if we didn’t have a job to do. I mostly went without weapons: the things I used most were made of magic, or available at a moment’s notice through magic’s pull. I did get a flashlight, though. Prosaic and not at all sexy.

For a giant monster snake, the uketna left very little trace of its passage. Grass and low-lying brush had already sprung back up, like the beast didn’t carry any of the mass something its size should. Or, more likely, like it wasn’t quite of the Middle World, the aspect of the spirit realms that most of human life took place in. Loosely speaking, in my experience, things like the uktena climbed up out of the Lower World, a place of powerful magics that hankered for the Middle World’s physicality. The Upper World’s denizens seemed more content to remain spirit creatures, though they weren’t above entering the fray every once in a while. Point was, the uktena might well not have slithered down the hill we were following; we might have just caught a glimpse of it slipping from one space to another in the Lower World, using a little stretch of the Dragon to get there quicker. If Morrison hadn’t seen it too, I might have thought I’d Seen into the Lower World for a few seconds, but even after everything we’d been through, my husband had the magical aptitude of a turnip. The uktena had been in our world, even if only for a moment. I slowed, frowning toward a river buried in the gorge, audible but nowhere near visible.

“What’s wrong?”

“I don’t think we’re going to find it on this plane.”

“Maybe that means Aidan is sa—”

I had to hand it to the man: he had reflexes like nobody’s business. I was halfway toward turning to him as he spoke, just far enough to glimpse the speed of his action and hit the deck. The shotgun came up and two blasts were fired above my head, straight into the uktena’s massive open jaws. I hadn’t even known it was there. And I should have: the Sight should have warned me even if nothing else did. The giant snake squealed and whipped away, slashing trees and air with one of its vast, wretched wings. I rolled to my feet with a sword in hand: silver-crafted and ancient, it had belonged to a god until I took it from him in fair combat. Gunmetal fire flew up its blade, the manifestation of my shamanic power, but as I dove forward to strike at the uktena, it vanished from my view. Half a heartbeat later Morrison and I were back to back, circling, and he asked what I was thinking: “Where the hell did it go?”

“I don’t know. I lost it. The Sight can’t See it.” I could See everything else just fine, all the brilliance of the night flaring with shamanic color, but there wasn’t even a blank space where the uktena hid. No, of course not. That would be too easy.

“The Sight can’t—then stop using the Sight!”

I mumbled, “Yes, boss,” which got a snort out of Morrison, and shut the Sight down.

It didn’t help. I still couldn’t see the uktena, or hear it, either. Now it was just ordinary dark with ordinary moonlight peeking through the ordinary trees. Still, at least this way I didn’t expect to be able to see it, which meant when it surged again—mouth closed this time, head raised but tilted forward so its antlers came for us first—I wasn’t quite as surprised. I grabbed for one of its horns, and caught a better look at the jewel between its eyes. Jewel, scale, something: it had depth like a faceted stone, but looked flat like a scale, and had that streak of blood red that seemed to sink right into the uktena’s head. I thought I could reach into it, and, stupidly, tried.

The uktena caught me in its antlers and flung me into the trees. I hit with a grunt and slid down, feeling shamanic magic wash through me to heal the contusions as fast as they appeared, although it didn’t make any instinctive effort to help me pull the air back into my lungs when I landed on the ground and knocked the wind out of myself. It had been a long time since I’d thought of the magic as something separate from myself, but some days I still thought it had some opinions of its own. Including commentary on what I deserved to suffer for my stupidity in a fight. Breathing, for example, was apparently optional.

I could see from my cheek-down position on the forest floor that Morrison was doing somewhat better than I was. He’d managed to grab an antler in the aftermath of me being thrown around, and had gotten on top of the uktena’s skinny neck, wrapping his legs around it to hold on with all his strength while he jammed one of his knives under the monster’s crystal and tried to pry it up. The uktena screamed, more offended by the attempt on its jewel than a shotgun blast to the gullet, but it couldn’t get to him: even its wings, beating furiously, couldn’t reach him.

They could, though, lift the uktena, and Morrison, off the ground. He cast me a wild-eyed look as they rose. I forced air back into my diaphragm and scrambled to my feet, breaking into a run before I was fully upright. There was moss underfoot, springy and soft. I whispered, “More?” to it, and the land surged beneath my feet, adding extra power to my upward leap.

I called my sword halfway through the air, clasping its hilt in both upraised hands, and let body weight and momentum drive it deep into the uktena’s chest. It was only dangling there in midair, hanging on for dear life to a blade ripping slowly down through the monster’s yellow belly, that it occurred to me that I had no idea at all where in a snake’s body the heart was located. I could have missed it by a country mile, and I didn’t think I’d have a chance to gut it from chest to tail in hopes of finding it.

Lucky for me—sort of—it didn’t even so much as scream, just suddenly fell out of the sky. On top of me, cool blood pouring over me in waves while it thrashed and twisted. I rolled, trying to get out from under it, and mostly got myself squished under another writhing coil. Morrison bellowed, then fell horribly silent, and any impulse to let the uktena ride out its death throes in peace left me. Even half-drowned in snake blood I could pull a psychic net together, and a great thing about magic is it doesn’t require leverage the way real-world things do. I wrapped the uktena in gun-blue steel strands made of my will and my power, and swung it to the side. It crashed into trees, sending leaves and branches raining down while I half-crawled, half-ran to Morrison’s side.

His skin had taken the tinge of someone deprived of oxygen, but he crossed his eyes at me when I landed at his side. A tiny laugh escaped me and I put my hand over his abdomen, sending a pulse of magic into the knotted muscle so it would release. He whooshed in a breath just like I had about two minutes earlier, and for a few seconds lay there getting used to breathing again. Then he unfolded an arm from underneath himself and held up a palm-sized jewel. “Ulunsuti.”

“Holy—you got it? You did it, you—” I looked toward the uktena, now shuddering with its last breaths, then back at Morrison with a stupid smile. “Only great heroes can kill the uktena.”

“I’m not the one who killed it.”

“Don’t be too sure about that.” I crawled over his hips and leaned down to kiss him. “The jewel didn’t tell me its name when I stuck a sword in the uktena. Ulunsuti,” I echoed. “If you look into it, it’s supposed to show you the past. Or the future.”

“I already know our past. And that we’re probably lying in a bed of poison ivy.”

“Look into it anyway. I saw a red streak when I looked in, when it was on the uktena’s forehead. What do you see?”

“Poison ivy, Jo.”

“If I can’t heal a little rash I have no business calling myself a shaman. What do you see, great hero?”

Morrison chuckled, lifting the crystal. It looked more like an enormous scale, off the uktena: no more than half a centimeter deep, and roughly triangular, with no visible facets after all, and made up of the colors of moonlit shadows. “A white streak,” he reported. “Not really white, though. Like white quartz. It catches the light.” He turned it, fascination pulling a smile to his lips. “It’s there no matter which direction I turn it, even on the thin edge. Nothing else, though, babe. I don’t have the eyes to see the future. You look.”

“Mmm-mmm. It’s your ulunsuti. Pretty sure there’s a ritual to hand it over to somebody else.” I called power, tracing the shape of an eye on Morrison’s forehead. It settled against his skin, glowing silver-blue, and I murmured, “Try again.”

He looked upward, like he could see his own forehead, then arched an eyebrow at me. “What happened to the standing on your feet trick?”

I sniffed, employing my best disdainful voice. “Give me some credit, James Michael Morrison. I have learned a thing or two over the years.”

Morrison laughed. “Pulling out full names, are we? Watch it. Yours is more of a mouthful than mine.”

“Mine is more of a mouthful than anybody’s. Go on, look, I want to know what you see.”

“What if I don’t want to see the future, Walker?”

I kissed his jaw. “Just this once. Just this once I think you do.”

He raised his eyebrows, then tipped the flat of the scale back toward himself. Moonlight caught it, glowing through, and I watched his expression go still, then stunned. He watched for a long time, long enough for me to chew a raw spot onto my lower lip, before he finally looked back at me, and said, slowly, “‘Any kid’s future’, Walker?”

“Well, who would want to risk it,” I whispered.

He dropped the crystal and rolled me into his arms, and in the end it turned out that even shamanic magic had a hard time getting poison ivy out of certain places.

the end